Andrew Boxer traces the assimilation policies, indigenous rights, and the changing relationship between the US government and Native Americans.

Andrew Boxer | Published in History Review Issue 64 September 2009

At the start of the twentieth century there were approximately 250,000 Native Americans in the USA – just 0.3 per cent of the population – most living on reservations where they exercised a limited degree of self-government. During the course of the nineteenth century they had been deprived of much of their land by forced removal westwards, by a succession of treaties (which were often not honoured by the white authorities) and by military defeat by the USA as it expanded its control over the American West.

In 1831 the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Marshall, had attempted to define their status. He declared that Indian tribes were ‘domestic dependent nations’ whose ‘relation to the United States resembles that of a ward to his guardian’. Marshall was, in effect, recognising that America’s Indians are unique in that, unlike any other minority, they are both separate nations and part of the United States. This helps to explain why relations between the federal government and the Native Americans have been so troubled. A guardian prepares his ward for adult independence, and so Marshall’s judgement implies that US policy should aim to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream US culture. But a guardian also protects and nurtures a ward until adulthood is achieved, and therefore Marshall also suggests that the federal government has a special obligation to care for its Native American population. As a result, federal policy towards Native Americans has lurched back and forth, sometimes aiming for assimilation and, at other times, recognising its responsibility for assisting Indian development.

What complicates the story further is that (again, unlike other minorities seeking recognition of their civil rights) Indians have possessed some valuable reservation land and resources over which white Americans have cast envious eyes. Much of this was subsequently lost and, as a result, the history of Native Americans is often presented as a morality tale. White Americans, headed by the federal government, were the ‘bad guys’, cheating Indians out of their land and resources. Native Americans were the ‘good guys’, attempting to maintain a traditional way of life much more in harmony with nature and the environment than the rampant capitalism of white America, but powerless to defend their interests. Only twice, according to this narrative, did the federal government redeem itself: firstly during the Indian New Deal from 1933 to 1945, and secondly in the final decades of the century when Congress belatedly attempted to redress some Native American grievances.

There is a lot of truth in this summary, but it is also simplistic. There is no doubt that Native Americans suffered enormously at the hands of white Americans, but federal Indian policy was shaped as much by paternalism, however misguided, as by white greed. Nor were Indians simply passive victims of white Americans’ actions. Their responses to federal policies, white Americans’ actions and the fundamental economic, social and political changes of the twentieth century were varied and divisive. These tensions and cross-currents are clearly evident in the history of the Indian New Deal and the policy of termination that replaced it in the late 1940s and 1950s. Native American history in the mid-twentieth century was much more than a simple story of good and evil, and it raises important questions (still unanswered today) about the status of Native Americans in modern US society.

Between 1887 and 1933, US government policy aimed to assimilate Indians into mainstream American society. Although to modern observers this policy looks both patronising and racist, the white elite that dominated US society saw it as a civilising mission, comparable to the work of European missionaries in Africa. As one US philanthropist put it in 1886, the Indians were to be ‘safely guided from the night of barbarism into the fair dawn of Christian civilisation’. In practice, this meant requiring them to become as much like white Americans as possible: converting to Christianity, speaking English, wearing western clothes and hair styles, and living as selfsufficient, independent Americans.

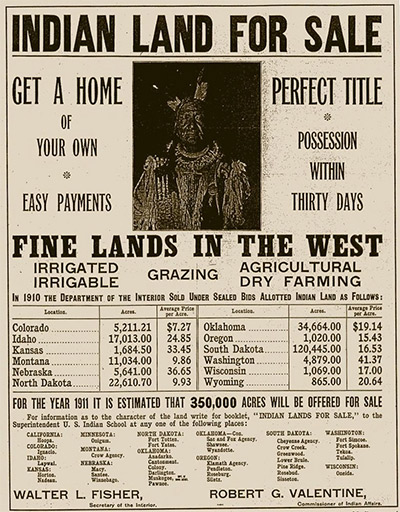

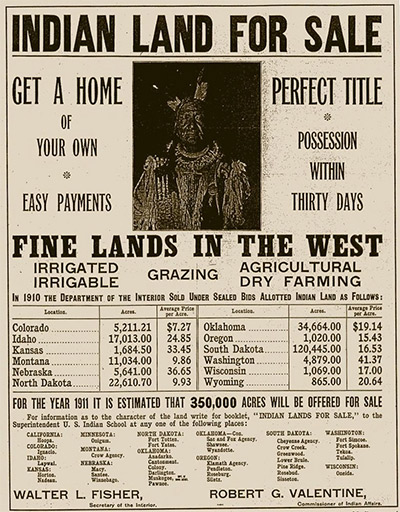

Federal policy was enshrined in the General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887 which decreed that Indian Reservation land was to be divided into plots and allocated to individual Native Americans. These plots could not be sold for 25 years, but reservation land left over after the distribution of allotments could be sold to outsiders. This meant that the Act became, in practice, an opportunity for land-hungry white Americans to acquire Indian land, a process accelerated by the 1903 Supreme Court decision in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock that Congress could dispose of Indian land without gaining the consent of the Indians involved. Not surprisingly, the amount of Indian land shrank from 154 million acres in 1887 to a mere 48 million half a century later.

The Dawes Act also promised US citizenship to Native Americans who took advantage of the allotment policy and ‘adopted the habits of civilized life’. This meant that the education of Native American children – many in boarding schools away from the influence of their parents – was considered an essential part of the civilising process. The principal of the best-known school for Indian children at Carlisle in Pennsylvania boasted that his aim for each child was to ‘kill the Indian in him and save the man’.

The 1924 Citizenship Act granted US citizenship to all Native Americans who had not already acquired it. In theory, this recognised the success of the assimilation policy, but the reality was different. Indians were denied the vote in many Western states by much the same methods as African-Americans were disenfranchised in the South. The Meriam Report, published in 1928, showed that most Indians lived in extreme poverty, suffering from a poor diet, inadequate housing and limited health care. Schools were overcrowded and badly resourced. The Meriam Report, while accepting that government policy should continue to enable Indians to ‘merge into the social and economic life of the prevailing civilization as adopted by the whites’, rejected ‘the disastrous attempt to force individual Indians or groups of Indians to be what they do not want to be, to break their pride in themselves and their Indian race, or to deprive them of their Indian culture’.

This new approach to Native Americans was enthusiastically endorsed by John Collier, who became Commissioner for Indian Affairs in 1933. Collier, a white American, believed that Native American community life and respect for the environment had much to teach American materialism, and he became passionately determined to preserve as much of the traditional Indian way of life as possible. In particular, he wanted Native American reservations to be permanent, sovereign homelands. The centrepiece of his new policy was the 1934 Indian Reorganisation Act (IRA) which ended the policy of allotment, banned the further sale of Indian land and decreed that any unallotted land not yet sold should be returned to tribal control. It also granted Indian communities a measure of governmental and judicial autonomy.

The IRA was vitally important in arresting the loss of Indian resources, and Collier, by directing New Deal funds towards the regeneration of Indian reservations, successfully encouraged a renewed respect for Native American culture and traditions. Not surprisingly, some historians sympathetic to Native Americans have placed him and the IRA on a pedestal. Vine Deloria Jnr described the IRA as ‘perhaps the only bright spot in all of Indian-Congressional relations’ and Angie Debo praised Collier as ‘aggressive, fearless, dedicated . an almost fanatical admirer of the Indian spirit’.

Other historians, however, have argued that the IRA was highly controversial and, in many respects, unsuccessful. The Act assumed that most Native Americans wanted to remain on their reservations, and so it was vigorously opposed by those Indians who wanted to assimilate into white society and who resented the paternalism of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). These Indians criticised the IRA as a regressive ‘backto- the-blanket’ policy that aimed to turn them into living museum exhibits. Although the IRA was accepted by 174 out of a total of 252 Indian tribes, a number of the larger tribes were among those who rejected it. Historian Lawrence Kelly tells us that ‘of approximately 97,000 Indians who were declared eligible to vote, only 38,000 actually voted in favour of the Act. Those who voted against it totalled almost 24,000.’ Nor did the electoral rules add to its credibility. Peter Iverson has pointed out that ‘the practice of counting no vote at all as a vote in favour of the measure helped swing close elections, especially on smaller reservations. The Santa Ysabel reservation in California was counted as giving the Act a 71- 43 margin of approval, but only nine persons there actually voted for [the IRA].’

Moreover, Collier’s policies, through no fault of his own, failed in the most crucial areas of all. The erosion of Indian land as a result of allotment had created a class of 100,000 landless Indians, adding to the problems of the reservations whose best land had been sold off since 1887. Few could become self-sustaining economically and Collier succeeded in adding only four million acres to their land base. Furthermore, the annual budget of the BIA was not large enough to cope with the demands of economic development for the reservations, let alone provide adequate educational and health facilities.

The Second World War further damaged the Indian New Deal. The BIA office was moved from Washington to Chicago in 1942 and its budget was cut as federal resources were devoted to more urgent war-related activities. The reservations lost a further million acres of land, including 400,000 acres for a gunnery range and some for the housing of Japanese-American internees.

The experience of war also transformed the lives and attitudes of many Native Americans. There were approximately 350,000 Native Americans in the USA in 1941, of whom 25,000 served in the armed forces. This was a higher proportion than from any other ethnic minority. Recent films have celebrated some of their best-known contributions. Clint Eastwood’s 2006 film Flags of our Fathers explored the tragic life of Ira Hayes, one of the men featured in the famous photograph of six Marines raising the US flag over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima. The 2002 film Windtalkers dealt with a group of Navajo whose language provided the US military with an indecipherable code.

A further 40,000 Native Americans worked in war-related industries. For many, this involved a permanent relocation to the cities and a willingness to assimilate into mainstream white culture. Collier himself recognised that the federal government would need to change its Native American policy fundamentally as a result of the war. In 1941 he pointed out that, ‘with resources inadequate to meet the needs of those already [on the reservations], the problem of providing employment opportunities and a means of livelihood for each of the returning soldiers and workers will prove a staggering task’. The following year he even hinted at a return to the policy of assimilation. ‘Should economic conditions after the war continue to offer employment opportunities in industry, many Indians will undoubtedly choose to continue to work away from the reservations. Never before have they been so well prepared to take their places among the general citizenry and to become assimilated into the white population.’

The Second World War profoundly changed the ideological climate in the United States. The nation had just fought a major war to destroy one collectivist ideology – Nazism – and the onset of the Cold War in the late 1940s made most Americans worried about the power and ambitions of another – Communism. Americans began stridently trumpeting the virtues of individual freedom against the collective ideology of the USSR. Collier’s policies were regarded with intense suspicion, and the IRA came to be seen as a domestic version of socialism, or even communism. Many conservative Congressmen had never liked it because they believed that the autonomy it granted to Native American communities gave them special privileges. Furthermore, Collier’s policies seemed to perpetuate the status of Native Americans as wards of the federal government who would require continued supervision and economic support from the BIA, which, to conservative Congressmen, was an expensive and unnecessary bureaucracy funded by white taxpayers. The IRA was also criticised by the National Council of Churches for the support it gave to Native American religions. In January 1945 Collier, worn down by the growing hostility to his policies, resigned as Commissioner.

The notion that it was time to terminate the wardship status of Native Americans and wind up federal responsibility for their welfare became increasingly popular in Washington in the postwar years. This would mean that BIA could be abolished, the reservations broken up, Indian resources sold off and the profits divided among tribal members. Indians would become just like any other Americans – responsible as individuals for their own destiny.

In this context, Collier’s critics could blame his policies, rather than inadequate federal funding, for the economic backwardness of the reservations. The IRA, by returning the land to communal ownership and making it inalienable, had limited the property rights of individual Indians. In the words of historian Kenneth Philp, ‘this well-intentioned [IRA] policy threatened perpetual government supervision over many competent individuals, made it difficult to secure loans from private sources, and discouraged Indians from developing their land resources’. Furthermore, the wartime migration of many Indians to the cities appeared to suggest that what many Native Americans themselves wanted was participation in America’s booming postwar industrial economy rather than a life of rural squalor on the economically deprived reservations.

In 1948 William Brophy, Collier’s successor as Commissioner, began a policy of relocating Indians – initially from two tribes – to the cities where the job opportunities were better than on the reservations. This programme was gradually expanded and by 1960 nearly 30 per cent of Native Americans lived in cities, as opposed to just 8 per cent in 1940. Although the BIA provided some financial support and advice for relocating Indians, it reported as early as 1953 that many Native Americans had ‘found the adjustment to new working and living conditions more difficult than anticipated’. Securing housing, coping with prejudice and even understanding the everyday features of urban life such as traffic lights, lifts, telephones and clocks made the experience traumatic for many Indians. Not surprisingly, many suffered unemployment, slum living and alcoholism. Federal funding for the relocation project was never sufficient to assist Native Americans to cope with these problems, and many drifted back to the reservations.

The first step towards terminating the reservations came in 1946 when Congress, in part to reward Native Americans for their contribution to the war effort, set up the Indian Claims Commission to hear Indian claims for any lands stolen from them since the creation of the USA in 1776. The Commission was initially supported by the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), a pressure group formed in 1944, because they welcomed a federal initiative to deal with long-standing grievances. However, it was clear that the Commission would provide only financial compensation and not return any land. The federal government regarded the Commission as the first step to ‘getting out of the Indian business’. This was clearly how President Truman saw it: ‘With the final settlement of all outstanding claims which this measure ensures, Indians can take their place without special handicaps or special advantages in the economic life of our nation and share fully in its progress.’ The original intention was for the Commission to sit for five years, but there were so many claims that it remained in existence until 1978.

In August 1953, Congress endorsed House Concurrent Resolution 108 which is widely regarded as the principal statement of the termination policy:

It is the policy of Congress, as rapidly as possible, to make the Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States, to end their status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship.

In the same month Congress passed Public Law 280 which, in California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon and Wisconsin, transferred criminal jurisdiction from the Indians to the state authorities, except on certain specified reservations. Congress also repealed the laws banning the sale of alcohol and guns to Indians. These measures could be justified as merely bringing Indians into line with other US citizens but, as one historian has observed, ‘the states were not as eager to control the reservations as the advocates of termination had expected’. In some Indian areas law and order disappeared altogether.

Many Native Americans were alarmed about the termination policy. One Blackfoot tribal chairman pointed out that, ‘in our language the only trans-lation for termination is to “wipe out” or “kill off”’. But in Washington, it was seen in terms of freedom and opportunity. Senator Arthur Watkins of Utah, the principal Congressional advocate of termination, claimed in a 1957 article that it could be compared to the abolition of slavery: ‘Following in the footsteps of the Emancipation Proclamation of 94 years ago, I see the following words emblazoned in letters of fire above the heads of the Indians – THESE PEOPLE SHALL BE FREE!’

These remarks were, of course, self-interested. Termination would open up yet more valuable Indian land and resources to white purchasers. This explains why, in the Congressional committee hearings on termination, there was considerable controversy over the future of the first reservations selected, especially those of the Menominee of Wisconsin and the Klamath of Oregon who had large land holdings and valuable forestry and timber resources.

Termination proved very hard to resist. Opponents who stressed the backwardness of the reservations and the inability of individual Indians to cope without continued federal support only confirmed the Congressmen in their conviction that the IRA had failed and that a new policy was necessary. Even the lack of adequate facilities for Native Americans could be used as evidence that termination was necessary. When a Congressman from Texas tried to argue against the termination of the small reservation in his district, he had to admit that the federally-maintained Indian school attended by the Native American children was over 500 miles from their homes, and that it made more sense for them to be educated locally alongside white children.

The NCAI was also in difficulties because many Native Americans favoured termination. These were mostly the half-blood Indians who had moved to the cities and, in many cases, adopted the values and lifestyles of the white majority. They stood to gain financially if the valuable land on their reservations was sold and the money divided among tribal members. As Helen Peterson, a member of the Oglala Sioux and a former director of the NCAI, later recalled:

In the NCAI office we did all we could to support, encourage, and back up those people who dared to question termination, but it was pretty much a losing battle. The NCAI was in a tough spot. We were deeply committed to respecting the sovereignty of a tribe. Did the NCAI want to oppose termination even when the people involved wanted it? We never really came to a final answer on that question.

The NCAI was able to prevent the termination of some tribes, including the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, but not the resource-rich Menominee and Klamath. However, the pace of termination slowed in the mid-1950s as it became clear that many Indians had not been properly consulted and few fully understood its implications. In 1958 the Secretary of the Interior, Fred Seaton, declared that ‘it is absolutely unthinkable . that consideration would be given to forcing upon an Indian tribe a so-called termination plan which did not have the understanding and acceptance of a clear majority of the members affected’. In the 1960s the policy was abandoned.

Judged by numbers alone, the impact of termination was small. It affected just over 13,000 out of a total Indian population of 400,000. Only about 3 per cent of reservation land was lost. But it caused huge anxiety amongst Native Americans and had the ironic result of stimulating the formation of the ‘Red Power’ protest movement of the 1960s. It remains an emotive issue among historians sympathetic to Native Americans. Angie Debo called it ‘the most concerted drive against Indian property and Indian survival’ since the 1830s. Jake Page concluded that it had been ‘an utter betrayal of trust responsibilities by the federal government’, and Edward Valandra has claimed that ‘termination increasingly resembled extermination’. However, it is difficult to see what policy, in the context of the early Cold War, could have replaced it. Even today, neither the Native American tribes themselves, nor the federal government, have successfully resolved exactly what the status and identity of the original inhabitants of the north American continent should be.

Andrew Boxer was for many years Director of Studies and Head of History at Eastbourne College. He is an A-level examiner for OCR and the author of a number of textbooks on aspects of modern British and European history.